Two

photographic interpretations of the bombing of the AMIA

Arizona State University

There are two irrefutable facts

regarding the recent social history of Argentine Jews: 1) the devastating

bombing of the AMIA on July 18, 1994, which left 85 dead and 300 wounded; and

2) the fact that no one has ever been brought to justice for this massacre and

that, indeed, basic facts discovered by Argentine and Israeli investigators

have never been revealed to the public or the families of the victims, despite

the many leaks of information and common beliefs about those responsible. The

AMIA disaster remains very much of an unhealed wound in the collective memory

of Buenos Aires. While one could say that it is just one more unresolved crime

of significant sociohistoric dimensions that Argentines have had to cope with,

one more appendix to the frightful cycle of tyranny throughout national history,

the bombing of the AMIA has had particular resonance for the Jewish community.

And taking place as it did in the heart of the Once neighborhood, the legendary

center of the community, brought with it a paradigm shift: in one sense the

Once has never been the same since, and in another sense Argentine Jews have

experienced a much altered relationship to their society.

There is now a significant

bibliography of cultural production relating to the AMIA bombing, and it stands

alongside important projects such as the Daniel Burman et al. series of ten ten-minute docudrama shorts, 18-J

(2004) on the impact of the bombing on the daily lives of those who live and

work in the Once. I would like here, however, to discuss two important

photographic projects focusing on the AMIA bombing. One project involves

conventional photography, the other a return to the legendary popular genre of

the fotonovela. One is an exercise in

memory construction, the other a metacommentary on the limits of photography as

cultural production.

Santiago Porter's collection of

photographs of personal belongings of the victims of the bombing, La ausencia (2007) details the impact of

a major event on the lives of ordinary people through the construction of a

dossier grounded in eloquent pathos. (1) Synecdoche (the signification by the

part for the whole) and metonymy (the important associative or collateral

detail that summarizes an entity) are two of the most powerful rhetorical

strategies to be used in the representational codes of language. While

customarily identified with verbal language, synecdoche and metonymy are

unquestionably at work in other cultural languages: in the case of Porter’s

book, photography.

The Argentine

novelist Marcelo Birmajer speaks, in his introduction to the twenty images by

Porter, of how the bombing of the AMIA, which effected the total destruction of

the five-story building, produced the disorder of dismembered bodies, burnt and

water-damaged books, and the rubble of the destruction of the building, cars,

and surrounding buildings. In his view, Porter's photographs restore an order

to life against the chaos produced by the terrorists-assassins. And, one might

add, the fact that not one single person has been brought to justice for this

atrocious act of anti-Semitism in the Latin American country with the largest

Jewish population, remains as an aching need for such restoration of order (see

AMIA: la verdad imposible).

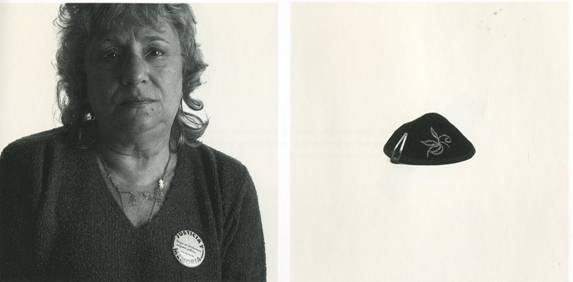

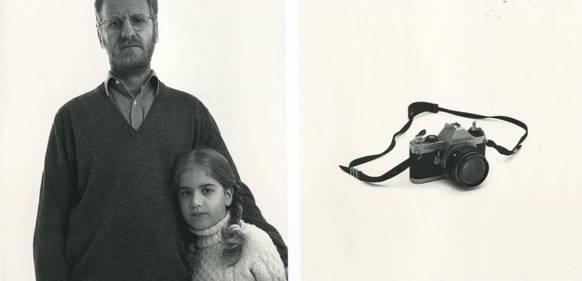

Porter's are

reproduced as high quality 24x20 cm. stark white panels, with the actual image

composed of two juxtaposed photographs, each against a champagne-colored

background. There is a clear unifying structural principle. Of the two

juxtaposed photographs, the one on the left is of a relative of one of the 85

victims (in five cases, more than one person is involved); the one on the right

is some personal effect of the victim that the relative retains as a vivid

memory of the lost loved one. All manner of relationships are represented:

parents who have lost a son or daughter; sons and daughters who have lost a

parent; widows and widowers; brothers and sisters; even, in one case, an

in-law. Surely, if one remembers that Jewish society is a communal culture—“life

is with people,” as the saying goes—one in which individuals identify

themselves in relationship to the community bound by laws, customs, and

traditions, Porter's array of individuals linked to victims by principles of

social connection provides one important level of the restoration of order.

To be sure,

one can argue that there are many Argentine Jews who have only a tangential and

tenuous link to traditional Jewish life, but it is safe to assume that the

employees of the AMIA—the bulk of the victims—were among those who continued to

have an investment in traditional Jewish values. In this sense, each of the

victims and each of the survivors are synecdoches of Jewish life in Buenos

Aires: actors in a social drama whose cohesiveness was challenged by the 1994

bombing. The extensive cultural production relating to the 1994 bombing, of

which Porter's dossier is one more eloquent entry, is alternatively an

ideologically grounded response to the challenge and, at its best, an

analytically driven one.

The juxtaposed

images of the effects of the victims are, in the main, mundane ones, whether

they are items that the victims had in their possession at the time of their

death and that were recovered from their bodies, or whether they are items that

they left behind on the day they went to work or to conduct personal business

at the AMIA (some were killed by the car bomb because they happened to be in

the vicinity of the AMIA rather than in it). These items, then, become

metonymies of their person, and, characteristically, they are principally

everyday items, such as a kippah, a teacup, a doll, a leather jacket, a school

uniform, work utensils, a wrist watch, a set of keys. Some of the items are

mundane; some of them are important effects, such as the kippah or work utensils.

The English word "effects" captures very well the sense of integral

relationship of these items, which, if only seen in isolation, would be

inanimate artifacts. But as significant extensions of the everyday, material

life of those who possessed them, these effects are the detail that remits the

viewer to the wholeness of their humanity, which has been shattered by the

circumstances of their death.

Porter's

photographs contain an element of pathos, because the viewer understands the

unresolved emotions, the melancholia, that the survivors must experience

vis-à-vis these inert items. One could examine only the images on the left of

each layout as a gallery of Jewish subjects in Buenos Aires. Likewise, one

could examine only the objects on the right as an inventory of a segment of

Argentine material reality in 1994. But viewed together, the effect is that of

a Jewish society that can forget neither the event nor its victims: the absence

(which, of course, in the first instance refers to the absent victims) of the

title is, in fact a permanent presence.

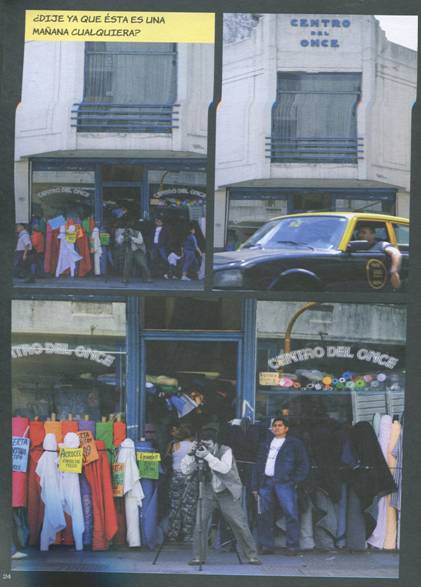

Stavans's and Brodsky's project,

Once@9:53, takes a different tack,

reviving the venerable genre of the fotonovela. While the graphic novel has

been prospering in Buenos Aires, the fotonovela is now very much of a forgotten

format, its reality effect presumably more efficiently achieved via television,

the internet, and cellphone imaging. Since one of the principal points to be

made by Once@9:53 (the title, of course, references the exact time of

the bomb blast) is the profound effect of the AMIA bombing on life in the Once,

the decision to construct a text based on an iteration of images of the

neighborhood through the rapid accumulation of images that sophisticated

photography enables provides a revalidation of the rhetorical possibilities of

the fotonovela. Ilan Stavans, a Mexican scholar and writer based in the United

States, brings to the project as author of the text his enormous familiarity

with the genre in Mexico, where it is still a viable product. Marcelo Brodsky,

as one of Argentina's most innovative photographers, with a distinguished

record of work on human rights issues and neofascist tyranny, provides the

photography for Once@9:53.

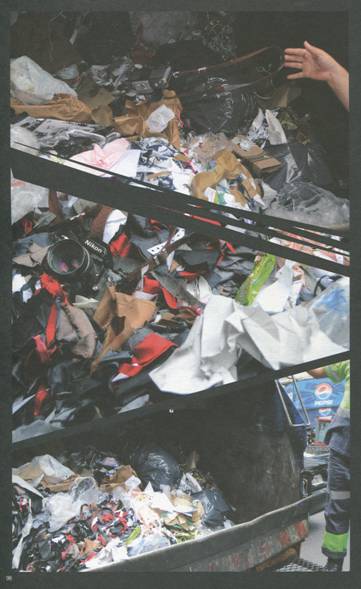

The text is organized around a

fundamental metaphotographic conceit: a photographer who is engaged in taking

images in the Once on the morning of July 18, 1994, captures with his camera a

young woman who first draws his attention because she is so attractive and then

because she is acting rather strangely. At the same time, he also captures a

suspicious-looking group of individuals with whom the young woman seems to have

some relationship. The photographer sees both the men and the woman hurriedly

getting into a waiting van. It is this van, laden with bombs, that will

ultimately crash into the AMIA and produce the lethal explosion that reduces

the imposing building to rubble. Although the photographer has captured the

suspects on film with his camera, one of them knocks him out. Just as he

recovers a few moments later and rises to his feet, dangling his camera from

its strap, another man rushes by him, grabs the camera, and tosses it in a

garbage truck just as the latter proceeds to compact its load. Presumably, the

camera is crushed to bits and its images forever destroyed. Although a few

moments later the explosion takes place, no visual record remains of those

responsible for it.

Once@9:53 is heavily ironic, since the

reader knows, in ways in which the photographer cannot, the inevitability of

the narrative arc that is relentlessly measured throughout the text by a series

of time markers and by a repeated negatively exposed map of the Once. These

elements remind the reader of the spatial scope of massacre that cannot be

prevented because, tragically, there is no way for anyone to read the signs

which are there materially (i.e., they are being captured by the photographer),

but which no one has at the time the key to interpret. There is a certain

dimension of apocalyptic teleology in this narrative, not just because the

dénouement of the story is foretold by the reader's familiarity with a historic

event (and, indeed, Stavans and Brodsky would have a text of no

sociohistorical significance if the reader did not already know that event

had—will have, by the time the reading of it is completed—already taken place),

but because it is foretold by signs in the text that only make sense with the

dénouement: a man walking by reading the Koran, a rather maniacal rabbi

predicting the end of time, a swastika suddenly spotted in a store window in

the heart of the Jewish quarter, a canary that falls dying from the sky. These

are all portents the photographer records but cannot interpret, even though the

reader knows ironically that they are there as part of an inevitable historical

climax that has already taken place.

Another metaphotographic

dimension of Once@9:53 is the

photographer's boast that a photographer sees what others cannot see. There is

certainly an intertextual reference here to Julio Cortazar's short story, “Las

babas del diablo” (from the 1959 collection Las armas secretas), where a

photographer has captured what others were unable to see, but who, seeing what

he has seen subsequent to its taking place, is powerless to intervene in the

act of violence his camera foretells: like Stavans's and Brodsky's

photographer, art is futile in the face of what will, inevitably, take place. There can only be the

melancholic abyss of individual impotence in contemplating that history: “Antes

y después de esa mañana cualquiera en que se escarbaron nuestras raíces y se

las expuso al sol, el Once ya no es el mismo, y yo tampoco.”

And yet, despite the

teleological pessimism that overshadows Once@9:53, the project is not without

its celebratory dimension, especially in the long aside in which the

photographer visits the rotisserie/bakery his own parents once frequented, an

icon of the permanence of Jewish culture in the Once. There is a brief

encounter between the photographer and Brodsky, who informs him he is preparing

a fotonovela. Brodsky's

daughter Valentina plays the role of the strangely nervous young woman, while

Marcelo Birmajer, the best contemporary novelist of the Once, comes to the

photographer's aid when he is knocked out by one of the suspects. Finally,

Stavans himself plays the maniacal rabbi who predicts that something strange is

going on and who, after the blast has taken place, announces that the end of

time has come. These details serve to make Once@9:53 less of the somber

narrative it might have been. Also worthy of note is the fact that although the

actual event took place in the middle of winter, Brodsky’s photographs are more

spring-like in nature. And by connecting the 1994 event with the present through

the use of current biographical markers, the text ends up confirming that, after

all, the Once is in fact an eternal presence in the life of the city.

Photography is a uniquely strong

form of cultural production in Argentina, and important Jewish names have long

been associated with it, both in representing Argentine Jewish society to its

members and in representing that society to the larger national community

thanks to the enormous public response to the power of the photographic image.

Moreover, photography in Argentina has served as a powerful tool in the process

of analysis of contemporary Argentine society, with specific emphasis on social

issues (see Foster, Urban Photography).

Both of these texts produce extremely valuable and highly creative contributions

to the necessarily ongoing conversation regarding July 18, 1994. Porter’s

volume involves a much more conventional utilization of photography, while the

Stavans-Brodsky project is not without its problematical dimensions. Many

readers might consider the fotonovela

lacking in sufficient gravitas for

such a tragic event as the AMIA bombing. As Herner has shown, the fotonovela, especially in the Mexican

tradition from which Stavans comes, is historically associated with barely

literate readers who are accustomed to sensationalist narratives (see also

Foster, “Verdad y ficción”). Indeed, Once@9:53 could be accused of trivializing the AMIA

bombing by utilizing such a low-brow format. However, I would argue that it is

possible to view the practices of the fotonovela

as useful to portray the banality and everyday commonness of life in the Once,

as in any society, on the verge of the bombing. Indeed, the enormous communal

destruction of the bombing is the way in which it disrupts such ordinary daily

life, which is grounded in the profound trust that nothing significant will

happen and that life will continue to progress incalculably one minute at a

time in its absolute ordinariness: at 9:52, life continues exactly as it is

expected to do,(2) and that ordinariness is most effectively captured by

making use of such an ordinary-life format like the fotonovela. Yet, as I have emphasized in my discussion of Once@9:53, the principal importance of

the Stavans-Brodsky project is to engage in a metacommentary as regards the

possibilities of photography in capturing and interpreting the complexities of

sociohistorical experience. In this sense, it is important to consider the

potential effectiveness of the juxtaposition between the sense of impotence of

the photographer in this regard and the momentous occurrence that suddenly jars

the everyday, ordinary life of the Once that he has been able/not been able to

witness and record with his camera.

Notes

(1)

This section on Porter’s

photographs is an

extended version of a review that I published in Chasqui 38.1 (05/2009).

(2) I am grateful to my colleague Kenya Dworkin for this

observation.

Works

Cited

AMIA: la verdad imposible: por qué el

atentado más grande de la historia argentina quedó impune. Ed.

Roberto Caballero. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 2005.

18-J. Dir. Daniel

Burman, et al. Buenos Aires, Aleph

Productiones, et al., 2004. Dur.: 100

min.

Foster,

David William. Urban Photography in

Argentina; Nine Artists of the Post-Dictatorship Era. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland

Publishing, 2007.

Foster,

David William. “Verdad y ficción en una fotonovela mexicana: la duplicidad

genera el texto.” Confluencia 2.2

(1986): 50-59.

Herner,

Irene. Mitos y monitos: historietas y

fotonovelas en México. México: Univerisdad Nacional Autónoma de

México/Editorial Nueva Imagen, 1979.

Porter, Santiago. La

ausencia. Buenos: Dilan Editotores, 2007.

Stavans, Ilan, and Marcelo Brodsky. Once@9:53. Buenos Aires: la marca

editorial, 2010.