|

Note: The name of this newsletter has been changed from Momentum to In Depth to provide further clarity about its focus.

Does one size fit all when it comes to courses and curricula?

One size rarely fits all in any domain, and certainly not in higher education. Like most faculty members, I have taught a range of courses, including ones geared toward nursing students, pre-allied health students, biology majors, medical students, biomedical engineering majors, and Neuroscience Ph.D. students at the Graduate Center. A single approach to teaching definitely did not fit this array of courses or the students in them.

There were, however, some features common to successful courses. For instance, the more the pedagogy engaged the students both inside and outside of class, the better it was for their learning, regardless of the level of the course. When writing was a significant part of the curriculum, having fewer students meant I could spend more time marking papers and giving feedback. Being able to call on students by their names always helped them feel more connected, recognized and accountable. It also helped make recommendation letters more authentic.

President Lemons Meeting with Student Leaders

But some features of curricula and pedagogy are not equally successful for all classes, and their efficacy is at least somewhat dependent on the type of class and the students served. Examples include a major reliance on lectures, extensive use of online resources, and a large number of students in a class. At Lehman College, there is wide adoption of fully or partially online courses, but I surmise there is also a lot of traditional lecturing taking place as well. There are relatively few large classes.

Since we are in the middle of strategic planning, and we are always seeking ways to better serve our students, I think it may be useful to examine two features I’ve just mentioned: the use of technology and class size. The students served by Lehman today differ in many ways from those present at its founding in 1967. In looking at these two features, I will discuss some examples at Lehman which expand the traditional pedagogical boundaries with successful results for the Lehman students of today.

Personal experiences with pedagogy

First, I’ll start with my own classroom experiences. I have taught some small classes with fifteen to twenty students, and I have taught classes with nearly two hundred students. Perhaps the most interesting to me was a course that had twenty-five students the first time I taught it in 1998. I designed that course, Physiological Processes, for the core curriculum of the new Department of Biomedical Engineering at The City College of New York. It was required for majors, and they usually took it as juniors or seniors.

I initially taught Physiological Processes in a traditional way, using a lecture format. At the same time the class sessions were highly interactive, with frequent quizzes, and students presented a number of case studies throughout the term. As I prepared to teach the course again, after a ten-year hiatus, I learned just before the term began that, instead of the twenty-five students I’d expected, there would be sixty-five. The changes I made in response to this larger class size might help inform some aspects of the question I began with: “Does one size fit all?”

The class met in the same room, and I used the same basic syllabus from when I had first taught it. But much had changed over those ten intervening years, including technology and a growing body of research on pedagogy. There was more evidence of the importance of employing active learning strategies to narrow achievement gaps, particularly for socioeconomically disadvantaged students, regardless of their race and ethnicity. In the 2011 paper, “Increased Structure and Active Learning Reduce the Achievement Gap in Introductory Biology1,” researchers at the University of Washington showed how changing from a traditional course structure to active learning made a huge difference among socioeconomically disadvantaged students who otherwise struggled in biology. The pedagogy they studied included regular quizzes, outside work students did to prepare for class, and the use of multiple-choice questions, answered in class, followed by discussions led by teaching assistants or undergraduate learning assistants.

President Lemons Teaching Physiological Processes

”Highly structured course designs,” they noted, “provide practice with problem-solving and reasoning skills that may be new to high-risk students in introductory college STEM courses. Specifically, active learning that promotes peer interaction makes students articulate their logic and consider other points of view when solving problems, leading to learning gains.”

Speaking of high-risk students, the profile of my students, too, had changed markedly since I first taught Physiological Processes. Admissions standards had been relaxed to expand enrollment in the major. Indeed, enrollment had almost tripled and as a result, there was a wider range of backgrounds and abilities in the class. The shift in demographics was exciting to me, and also challenging. I found there were not enough seats in the classroom, so I had all the tables removed and added more chairs. Oh, and it now had just one three-hour class session per week instead of the two it formerly had. No reflection was required for me to conclude this could not be run optimally as a traditional lecture class.

So, I set about “flipping” the class. In a flipped classroom, the work students traditionally do out-of-class, such as problem sets, is instead done at least partially in the classroom. In this way, students can work through material collaboratively with instructors and their classmates. This is often referred to as a blended learning approach. There is little or no lecture in class and instead students watch online videos and use other digital resources outside of class, so that they come to class with the background needed to work on problems and answer questions.

I could only just begin “flipping” the class that term, and those poor students had to put up with far more lecturing than was effective. But by the next fall when I taught it again, I had put all of the lecture material onto YouTube in ten to twelve-minute segments, usually four to six per week. I prepared workshop materials for the three-hour weekly sessions. I structured each class session to run in three segments, with subtopics for the week covered in each. After workshopping a subtopic for about forty minutes in small groups, students discussed the subtopic as a whole class, and then took an iClicker quiz. iClickers look like remotes but they are radio frequency devices which allow students to respond to questions instructors pose in class. The summed class-wide answers are projected in real time, so we all knew immediately when there was a conceptual challenge needing further discussion. After we had completed the discussion and quiz, we began working on the next subtopic.

To me, the dynamics that resulted were remarkable. First, every student was engaged for the entire three-hour period of time. And as they were engaged in their group discussions, I had the freedom to listen in, interject ideas, be a resource, and learn names. Students were predictably astonished that I knew all of their names within a week or two.

I can’t claim that every student loved the format. It does put students on the spot all of the time; there is no back of the room. I made sure to call on every student on a rotating basis during the class-wide discussions. I also had the ability to dynamically allocate time to topics as needed. The discussions and the iClicker quizzes let me know immediately if we needed to spend more class time on a given topic. I didn’t have to worry about getting through a lecture, because those were all available any time students wanted to view them on YouTube.

Student using technology outside of class

This course had both of the elements I highlighted earlier: technology and larger class size. I was able to actually improve the course quality as the class tripled in size, because I could use technology. Essentially, I ran my class 24/7. A rich set of web resources in addition to the YouTube presentations were all linked on the Blackboard site. Without technology, I could not have taught this class effectively. Using it, I could.

I give this personal example not to suggest that what I did will work for every class and every instructor. I know it won’t. I simply see it as an example of the reality that one size does not fit all, and this was an experiment, run over the span of almost twenty years, that demonstrated what could be done successfully in one particular course.

But enough of my experience. I was interested to find out if there were faculty members at Lehman applying approaches similar to what I’ve just described. After all, I didn’t invent them; I adapted them from examples of which I’d become aware. I am sure I have not discovered all of the similar applications like this at Lehman, and I would like to learn of others. For now, I would like to highlight two examples at Lehman that I have learned about, one in science and one in the humanities. One is Prof. Donna McGregor’s work in Introductory Chemistry, and the other is Prof. Naomi Zack’s instruction in Philosophy.

Two Lehman examples

Donna taught at Hunter College for five years before she came to Lehman in 2015. There, she taught classes that ranged in size from 125 to 800 students, so she was accustomed to designing courses with high enrollments.

As a researcher/scientist, Donna not only studies chemistry but also chemistry education. As she recently noted in a webinar offering strategies for faculty members curious about how to manage larger classes, there are a variety of active learning strategies that professors can employ. But implementing them could cause some trepidation and be overwhelming if you tried to do them all at the same time.

Donna’s General Chemistry class at Lehman is taught by a team. She is the lead instructor, and she is assisted by her three graduate Teaching Assistants (TAs) and Undergraduate Learning Assistants (ULAs). The class meets in a Gillet Auditorium twice a week and has an enrollment of 220 students. Prepared for questions they may be asked as a result of viewing video content at home, students come equipped with their iClickers, and chemistry problems are projected. Students work the problems, often with each other in impromptu small groups, then they register their anonymous answers and wait attentively to see how their collective class did on a particular topic. In one session, the correct responses ranged from twenty to ninety-three percent correct on individual questions.

Students working together on Chemistry problems

The students and their instructors can see, in real time, what percentage of the class got the right answer. As in my biomedical engineering class, that immediacy allows instructors to allot more class time to topics with which a high percentage of students are struggling. Teaching Assistants and Undergraduate Learning Assistants move around the room, asking who needs more help, talking through some of the more challenging parts of a particular question. Their presence turns a potential downside of this large class to an upside, where students actually get more individual attention than usual. Regardless of the class performance on a given question, there is a follow-up slide that explains the answer to help reinforce the concept.

A number of years ago, pass rates in this Intro Chemistry course were around 35-40 percent. The Freshman Year Initiative, which put beginning students into smaller classes, helped move the passing rates to 50 percent. Chemistry professors also added Supplemental Instruction and Peer Led Team Learning to boost outcomes. This most recent iteration of pedagogical change has produced further improvement, moving pass rates to around 80 percent, and 85-88 percent for first-time students. These improving outcomes demonstrate the importance of continually seeking more effective ways to build better instructional approaches that respond to changes in our student demographics. Each step along the way generated improvement without lowering standards. It is an inspiring example that has come about through the ongoing work of many professors over the years.

You can see from Donna’s experience, and my own, that there is a greater complexity when putting a flipped class together, but there is not necessarily more work in running it. There is a different kind of work, and a greater amount of coordination is needed in order to make that work successful.

You may be thinking, well, fine, it works in science. But what about in the humanities?

Prof. Naomi Zack has taught large classes at SUNY Albany, and at the University of Oregon. Her classes have enrolled as many as 400 students. She will teach a large Introduction to Ethics course at Lehman in the Spring 2020 semester.

Like Donna, she has a team of Undergraduate Learning Assistants. She notes that just because there is a large classroom does not mean that students don’t have a small group experience. She offers them the opportunity to discuss various components of assignments in small groups, since some students have difficulty addressing hundreds of their peers on their own behalf.

Naomi is one of two professors I know of in the Arts and Humanities who teaches a large lecture class. She mentions another benefit of large classes when she speaks of the students of color finding community with one another in large classrooms where faculty are predominately white. In addition to highly structured classrooms giving them practice with active learning and interactive instruction that demonstrably improves their retention of material, a higher enrollment class also offers a visually shared community to students which may also boost their problem-solving confidence.

One of the unexpected benefits of having Undergraduate Learning Assistants in a classroom, as both Prof. McGregor and Prof. Zack do, is that the ULAs themselves grow and develop markedly. This is by now a well-documented outcome nationally in many courses over almost twenty years. ULAs are much more like to be involved in research as undergraduates, succeed in their major, and apply and go to graduate school. They gain confidence in their disciplinary knowledge and develop leadership skills. That is a big added bonus.

Conclusion

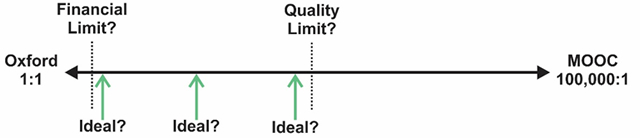

Coming back to the question, “Does one size fit all?”, I hope the answer is clear. Every curriculum and course is unique to some extent. The figure below shows a wide range of class size possibilities and, within that range, two limits, one on the left, the college’s financial capacity, and one on the right, based on the quality of the students’ experience and their success. Between those limits is a range of possible class sizes. Along that range, is there just one class size that is ideal? I doubt it. As we think about that, we have one overarching goal, and that is to make our students successful. If we are as close as we can be to the 1:1 professor to student ratio, Oxford style, students will probably have the highest probability of graduating, but we wouldn’t be able to educate very many students that way. If we go to the other extreme, we can teach very large numbers of students, but they would probably have a low rate of success. Our task is to find the sweet spot for each curriculum and course, thereby maximizing as much as possible the quality-quantity relationship with regard to class size.

In my experience, I could successfully offer the same course to twenty-five or sixty-five students, but not if I used the same approach. Technology allowed me to improve quality as the number of students tripled. It amplified my presence and allowed me to spend my quality time where it had the most impact. In some cases, technology can help us move rightward along the continuum, towards larger classes that serve more students, without compromising quality and student success. We could see an improvement in quality. If we can do that, we increase our impact. Many courses may be at their optimal size already and should not be expanded in a similar way. As I mentioned, increasing the size of a writing-intensive class would be inadvisable, and not serve students or instructors well.

We should be considering whether we have found the sweet spot for all of our courses at Lehman College. When we fail to do that we miss opportunities for our students. If a larger class can be created from a multi-section class, freeing up resources, those resources can be used to augment the class by supporting ULAs and/or TAs, and funding other course needs. It can also result in resources being reallocated to support some smaller classes where lower enrollment is critical for success. One size does not fit all, but the right size helps us do the most we can for our students.

I wouldn’t be telling the whole story if I left out a critical, and unavoidable aspect of using new pedagogies with technology to teach more students, and do it well. It takes a lot of work to convert a course to a new format. In my case it required over a year and many hours of my time. The only way to avoid that investment of time is to use the same pedagogy with a large enrollment class as with a small class. But that is not a winning solution. Provost Peter Nwosu has made available both funding and other assistance for faculty members who think their courses might serve a larger number of students. The College also has some excellent resources for assisting faculty members, including professional staff and faculty who are experts. A recent webinar featured them, and their three presentations are accessible:

- The “Why” of Teaching Larger Classes by Susan Ko, Faculty Development Consultant, Office of Online Education and Clinical Professor, Department of History, Lehman College

- The “How” of Teaching Larger Classes by Olena Zhadko, Director of Online Education (prepared by Naliza Sadik, Educational Technologist | Instructional Designer, Office of Online Education)

- The Faculty Experience with Teaching Larger Classes by Donna McGregor, Assistant Professor, Department of Chemistry, Lehman College

We plan to sustain this support for pedagogical and curricular innovation in the coming years, and the support will not be just for creating larger classes or ones with high DWIF rates. It’s worth noting that the draft FY21 CUNY budget being proposed also has funding for curricular innovation. Both the Lehman and CUNY funding will be for many kinds of pedagogical and curricular innovations that will increase student success.

I mentioned the study at the University of Washington at the beginning of this piece. There are many quantitative studies that document the impact of a wide variety of curricular innovations. We need to utilize the work of others like this. We also need to evaluate our own innovative work to show that it is successful. And when it is, we need to consider replicating it in other courses at Lehman, and share it inside and beyond CUNY.

Finally, I return again to the example Atul Gawande wrote about in “The Bell Curve.2” By his accounting, achieving outstanding results arose not from one magic bullet therapy, but from an environment that encouraged innovation, was tolerant of failure, and where there was a persistent determination to do better. One size does not fit all in that kind of environment; a variety of solutions produce the results. If we continue to work in that way, why shouldn’t Lehman College be nationally known as a place where pedagogical and curricular improvement is ongoing and highly effective in every area of study?

1 David C. Haak, Janneke HilleRisLambers, Emile Pitre, Scott Freeman, Science: 03 Jun 2011: Vol. 332, Issue 6034, pp. 1213-1216

2 Atul Gawande, The Bell Curve: What happens when patients find out how good their doctors really are?, The New Yorker, Dec. 6, 2004, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2004/12/06/the-bell-curve

Daniel Lemons

@LehmanPresident

Previous messages from President Lemons can be found here. |