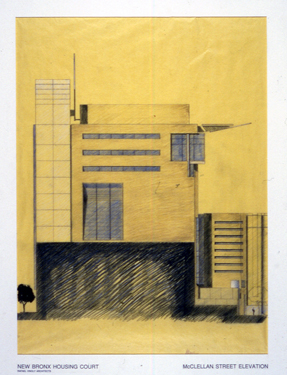

Bronx Housing Court

1118 Grand Concourse

Rafael Viñoly

1997

The 1997 Housing Court of Rafael Viñoly is one of very few contemporary buildings to appear on the Grand Concourse, and it usually minds its manners. Forced by a narrow site to rise considerably above the ordinary building line, it makes amends by trimming its southern wing to the height of an older six-story apartment house alongside, and tucking in its north frontage to match that of its other neighbor. The four rectangular volumes of which the building is assembled are surfaced with light-grey long, thin Roman bricks, and banded with horizontal striations and courses of glass block, in deference (it seems) to the patterned masonry for which the Concourse is famous.

Yet there are outbursts of sometimes-grotesque energy on the Uruguayan architect’s courthouse, starting with the swollen flagpoles and oversized translucent canopy at the entrance. The grey sobriety of the facades is challenged by swaths of reflective glass gridded by mullions. Asymmetrically poised above the entrance, for instance, is a broad window four stories high in a frame that stands forward from the building’s wall. Its function is to bring light into the stacked public lobbies of the interior, which have been given special attention in Viñoly’s plan as spaces where anxious litigants wait and settlements between landlord and tenant are often negotiated. The thirteen formal courtrooms, by contrast, are enclosed in the masonry wing to the south. Viñoly’s glass wall in effect unbuttons the conventional dignity of the judicial facade, lending confidence (we might say) to the public exercise of rights—a gesture especially appropriate for a housing court in the Bronx.

Aluminum-gridded glass reappears in the three-story box that sits at the top of the north wing, holding the judges’ library. Here the building’s anti-formal spirit expresses itself in a giant glass wedge, bearing an abstract clock-face, which angles out at thirty degrees from the façade, facing southwest. An antic take on the traditional courthouse clock, this one is conveniently readable from down, as well as across, the street. (There’s another clock-face on the uptown side.) The eccentric feature is meant to be visible from the distant Harlem River bridges, seizing an opportunity for attention no tall building on a ridge would be willing to forgo.

The Housing Court’s high skewed clock might also represent a final tip of the hat to the architecture of the Concourse Preservation District. Bronx residents may be reminded of a landmark near the opposite end of the boulevard, at Fordham Road: the 1951 Dollar Savings Bank, another narrow high-rise, whose square brick tower bears similar abstract clock-faces.

David Bady

Photographs:

Rafael Viñoly Architects and Jeff Goldberg / Esto Photographics, Inc