Fort Schuyler

Captain I.L. Smith 1833-1838; Conversion to New York Merchant Marine Academy, 1934-38; Luce Library, William A. Hall, 1967

John Throckmorton, an English settler who was burned out in the same series of Indian raids that left Anne Hutchinson dead, gave his name to the peninsula which trails off the SE corner of the Bronx: Throggs Neck. The Neck ends in a small tongue of land—originally an island connected only at low tide—which stands at the point where Long Island Sound radically narrows into the East River. Today, O.H. Ammann’s spectacular suspension bridge (1961) passes high over the ship channel, its cables anchored in a concrete bulk on the Neck. In the nineteenth century, however, engineers were not concerned with spanning the seaway, but with closing it to hostile navies. Along with other major coastal cities, New York was gradually being ringed with fortified batteries of artillery overseeing its sea approaches.

The walls of Fort Schuyler, on Throggs Neck, were begun in 1833 and finished more than a decade later. Captain I.L. Smith of the Army Corps of Engineers planned and executed the difficult construction. (He received suggestions in the 1840s from an interested First Lieutenant of the Engineers, Robert E. Lee.) It was another eleven years before artillery—probably only a third of the planned complement of over 134 heavy guns—was mounted on the works. Its field of fire would be joined by that of Fort Totten, a mile away across the river in today’s Bayside, Queens, to interdict passage southwestward, toward New York harbor.

But when war actually arrived, in 1861-65, Fort Schuyler’s guns remained silent. The grounds were given over to other essential purposes: the training and embarkation of Union regiments, the internment of Confederate POWs, and, at McDougall Hospital, treatment of nearly 12,000 soldiers wounded on distant battlefields. At the end of the Civil War the personnel used for all these, and even the artillery garrison, departed, leaving Schuyler (built to house 1,250) manned by a dozen men. In the next half century there were sporadic changes in the fort’s armament, providing the emplacements and large guns that would be needed to deal with a new kind of enemy, a fleet of heavily armored “dreadnoughts”. But its threat happily failed to materialize, and by 1934 Schuyler, once considered “chiefest of all” the coastal defenses of New York, was turned over to the State for peaceful conversion.

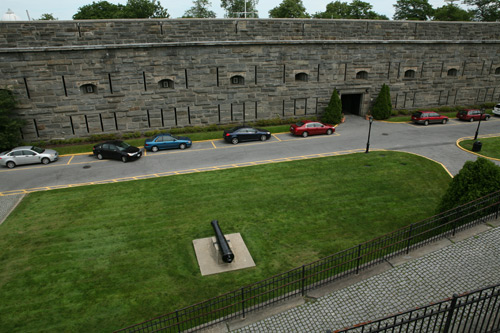

The exterior walls were left intact (although their protective crown of earthen rampart was carted away). The tiers of gun embrasures were glazed, becoming the windows of two floors of classrooms where undergraduates of the New York State Merchant Marine Academy would be trained as ships’ officers. Opened in 1938, the school eventually became the Maritime College of the SUNY system.

Today, the SUNYMC campus consists of many buildings, some original dependencies of the fort, others designed by Ballard and Todd in the ‘60s, as well as a training ship. But the main attraction for the visitor, competing with the transfixing waterfront panorama, is the old fort. Its architecture, although simplified, follows traditions of geometrical fortification that date back to Louis XIV’s designer Vauban and beyond. A hollow pentagon of irregularly coursed, rough-faced granite ashlar, its three eastern vertices (salients) have extensions (bastions) that make it possible for gunfire to sweep the faces of the fort clean of attackers. Two larger earthen bastions flank a rampart on the landside of the fort. Passing between them, the visitor crosses a drawbridge and enters a tunnel lined with menacing rifle slits. He emerges into the gorge, a narrow, walled open space, and then continues on through a protected gateway, or sally port, onto the drill field inside the walls, Saint Mary’s Pentagon. The climax of this spatially dramatic progress has been made ceremonial: stepping onto the field, cadets at the college come to attention and salute the flagpole at its center.

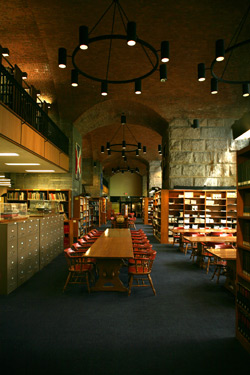

Saint Mary’s Pentagon was originally surrounded by colossal open brickwork arches forming the casemates protecting the guns. These formidable caverns have been covered with a curtain wall and divided halfway up by the mezzanine floor of the college, except at the fort’s northeast corner. There, in the Luce Library, an award-winning design of William A. Hall (1967), the visitor can stand beneath the impressive masonry at its full height, or climb to a balcony, once the upper gun tier, to watch approaching sailboats on the Sound.

David Bady

Photographer:

Tom Stoelker