Wildlife

Conservation Society

Bronx Zoo, Bronx Park south: Astor Court (formerly Baird Court), inside E. Fordham Road entrance Monkey House, 1901; Lion House, 1903; Bird House, 1905; Administration Building, 1910; Elephant House, 1911

Heins and LaFarge (with William Hornaday)

The fields, knolls and ponds of the former Lydig property along the Bronx River have “never been regarded as strikingly beautiful,” conceded William Hornaday in 1896. To the director of the yet unbuilt Bronx Zoo, however, this piece of recently-purchased city parkland offered a “really marvelous” variety of habitats for wildlife, exactly what he needed for a new kind of “zoological park” in which uncaged animals could range and prowl. But to maintain the effect of species in the wild, it would be essential to draw a sharp line between nature and civilization. As much as possible, the only structures in the southern and eastern parts of the park were to be animal shelters and rustic pavilions for strollers. Larger buildings, including the specialized housing required for birds, primates, and others, would be kept to an enclave in the north of lower Bronx Park, set apart from the natural landscape not just spatially, but by the “classic formality” of its design.

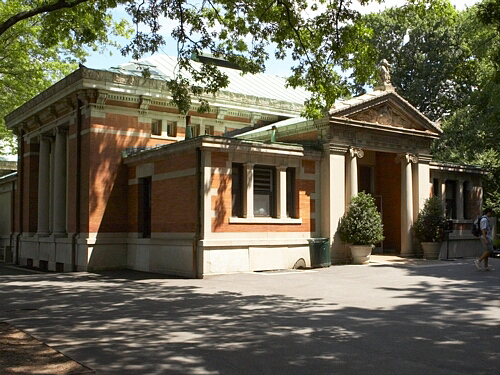

The result was Baird Court, begun in 1900 and finished within the decade, conforming (on its extremely small scale) to the “formality” of contemporary urban planning. Like the National Mall of the 1901 McMillan Plan for Washington, D.C., the court is organized as a vista framed by stylistically similar buildings with a uniform cornice line, and focused on a domed edifice. A raised rectangular terrace reaches southward from inside the Fordham Road gate (once the main entrance for carriages and motorcars), its central axis passing over lawns set between parallel tree-bordered walks. Symmetrically positoned on either side of this mall are handsome orange brick, limestone trimmed buildings with sloping roofs and heavy cornices. A square-plan Administration Building faces the L-shaped Bird House at the north end, with rectangular “Monkey” (actually Primate) and Lion Houses to the south. (The ”National Collection of Heads and Horns,” on the east side, is a later addition.) Architects Heins and LaFarge (who also designed the stations for New York’s new subway) have positioned/organized their buildings with an eye to the flow of crowds. The animal houses align their long sides with the axis of the court, but have entrances only at the narrow ends. The uninterrupted mall-facing exteriors of the lion and birds house are covered with cages. (Nervous monkeys were considerately exposed at the back side of their building.) Each of the four brick buildings is provided with a different version of a classical portico with columns and pilasters. Each is, to a different degree, ornate. The same Beaux Arts esthetic which expected symmetry and focus in plans had a taste for ripe embellishment on facades, as long as the decoration was nominally “classical.” So the houses are elaborated--in the case of the Lion House, encrusted-- with ancient and Renaissance devices: antefixes, cartouches, dentils, eggs-and-darts, and so on.

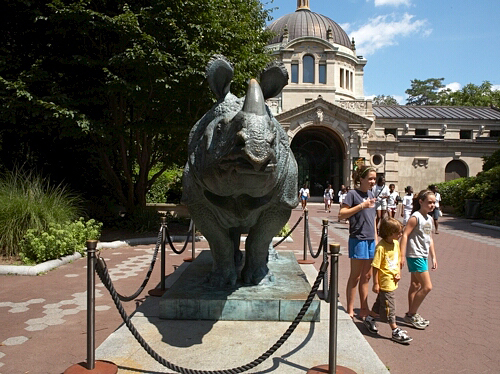

At the south end of the mall, the walks converge and pass into a plaza fronting the Elephant and Rhino House set crosswise to the court’s axis, a central grey limestone mass with long masonry wings, surmounted by a dome and lantern topping out at seventy-five feet: this is the “Capitol” of the zoo municipality. Patterned colonettes and polchromy on the lantern (originally continued in zig-zags of color on the dome) give the upper reaches a tinge of Spanish-Moorish exoticism, subsiding below into a bulky neoBaroque suited to the building’s ponderous residents. Unlike the other houses, this one is entered at the center of the facade, where a deep broken pediment and banded piers, one final variant on the classical portico, frame a huge arch with exaggerated voussoirs. It leads into a domed rotunda, joined on two sides by vaulted halls with hemispherical apses, where the large animals are housed. The flowing interior space is unobstructed by columns or cage bars, being made entirely of self-supporting Guastavino tile, glowing orange and herringboned in wonderful patterns. (The year after the Elephant House was opened, the Guastavinos completed their famous tile dome at Heins and LaFarge’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine.) The rotunda has another colossal opening on its south side, creating the sense that the central Elephant House is a double triumphal arch . (The effect has been improved by transparent coverings on the archways, originally closed by massive doors). Passing through the portals, zoo visitors know they are leaving the “civilized” for the “natural” remainder of the Park.

All the animal houses of the court make use of the work of so-called animaliers, sculptors who specialize in the accurate representation of fauna. The popularity of such pieces peaked in the late nineteenth-century, when America celebrated the survival of the fittest with lawn-sculptures of fighting beasts, and mourned the lost frontier with table-top bison and elk. The Zoological Society was committed to advancing the art, providing, for example, a “studio cage” in the Lion House where animaliers could work from live models, undisturbed by the public. And the classical features of the Heins and LaFarge buildings offered plenty of surfaces and platforms for sculptural decoration. Thus we find the foliated frieze of the primate house occupied by monkeys in low-relief, realistically distinguished by species, and an orangutan patriarch surrounded by his family lodged in the triangular tympanum. The cornice of the Lion House bulges with 38 high-relief heads of pumas, jaguars, leopards and lynx, the work of animalier Eli Harvey. He also provided the Lion House, the largest and most heavily ornamented of the forecourt buildings, with terracotta plaques from which burst seven startling life-sized lion, lioness, and tiger heads, most with jaws gaping in full roar. Their realism and animation is surely meant to contrast with traditional leonine ornament appearing elsewhere on the building: a lion spouting water in a fountain, lion-head fixtures with rings in their teeth, the pair of guardian lions at the sides of the north portico. A different interplay between realism and convention appears in three buildings featuring the work of A. Phimster Proctor, perhaps the country’s leading animalier. Proctor’s animals seem to have a penchant for taking the place of architectural elements. What appear at first to be acroteria on the Monkey House, abstract decorations standing on the apices of its classical pediments, reveal themselves to be free-standing life-sized sculptures of Hamadryas Baboons in characteristically watchful sitting positions. The sculpted elephant heads beneath the architrave of the Elephant House are not portrayed, as in some Eastern architecture, upholding the burden of the masonry. Instead, their trunks curve out and down in an elegant S, coming to rest on the wall in a naturalistic imitation of a “console,” a scrolled support bracket (which Heins and LaFarge have employed on all the other buildings of the court). Most inventive of all is the cornice of the Bird House, where upright cockatoos in a high-relief row alternate raised and lowered wings and crests, producing an avian version of a wave-patterned frieze (and, incidentally, what might be called a zoetrope sequence of beating wings). Perhaps unintentionally, the animaliers encourage nature to infiltrate the cityscape of Baird Court, and subvert some of its architectural dignity.

Baird Court is today Astor Court, re-named for Zoo benefactor Brooke Astor. The lions, birds and elephants have left their Beaux-Arts buildings for more hospitable environmental displays. Only the Monkey House retains some of its original resident species. The Elephant House has become the Zoo Center (also hosting small exhibits and a few Bactrian camel). As part of a 6.7 million dollar renewal of the Court, the Lion House, its outdoor cages sealed, has reopened as a showplace for the fauna of Madagascar.

The best known sculpture is not on Astor Court but at the Pelham Parkway entrance, where the Paul J. Rainey Memorial Gateway designed in 1926 by the well-known sculptor Paul Manship was installed in 1934. Made of bronze that over the years has turned a light sea green, the gates are a fantastic structure with two openings surmounted by openwork lunettes and bounded by tree like forms. Around the whole, some 22 different animals, including some former Zoo celebrities—Buster the giant Galapagos tortoise, Jimmy the Shoe bill stork, and Sultan the African lion—are used as decorative motifs.

David Bady

Photographs:

Abigail McQuade and David Bady